Laurence Williamson of Mid Yell I'm delighted to be here tonight speaking to you about Laurence Williamson. I've been fascinated by Laurence for many years, because he was so different from his contemporaries, and because he left so much evidence about what he thought about everything under the sun. Some of you will have read Laurence Johnson's biography of him. That marvellous book is full of letters and reminiscences, collected by someone who was Laurence Williamson's intimate friend and helpmate. There are also large collections of Laurence's unpublished letters elsewhere: lots in the Shetland Archives and the National Library in Faroe, and others in private hands here and there in Shetland. There are of course people still alive, although there are fewer and fewer of them every year, who knew Laurence. But it's doubtful if many people really knew him well, even in his heyday. Laurence was a withdrawn, quiet man; people were wary of him and what they regarded as his eccentricities. Laurence only flourished when he had a pen in his hand.

Laurence Williamson was born in Mid Yell in 1855, at Linkshouse, where his father was a general merchant. The family had strong connexions with and feelings about people and places in Fetlar. Laurence's father James had been born at Ruster, on the north side of Fetlar, in 1800; James Williamson and others knew stories about the Williamson family and their exploits for a hundred years before that. One of them, Daniel of Ruster, a member of the family from the early eighteenth century, was supposed to have been well-educated and intellectually very nimble. Laurence wrote down some notes about him about 1875. I quote them now as a fairly typical example of the kind of lore Laurence found fascinating. The Laird of Lunna had a tack of Fetlar and Daniel was factor for him. Daniel took the books and another man and went to Lunna to count. A storm came on and they got ashore under some high banks, but lost the boat and the books and all that was in her. They climbed till they came to a hollow of the banks but could get no farther. Daniel was robust and well clad, the other was neither and that night said to Daniel that he would die tonight. They were there a night and day, till 3 men came around the banks seeking sheep and saw them and got a rope and let down. They were so exhausted they could hardly fasten it round them but were drawn up. [They went] to the Laird of Lunna's house and were entertained there. The Laird said Fetlar had suffered a great loss by the loss of the books, but Daniel said if he got a room and writing material and 7 days respite he would try to remedy it. It was granted and he sat at his task till the seventh day when the Laird came in and said he must leave it or he would out wear himself. But he refused till he found out small things he had lost. At last he cried it is a pound of tobacco. Fetlar is clear. He had rewritten the books from memory. Laurence had a life-long obsession about what his sister May sarcastically called 'God's chosen people': the Williamsons of Fetlar and the families of Fetlar in general. He actually buried poor May in Fetlar, and he arranged to have himself interred there as well. But I think that Laurence had far deeper roots than he realized in Yell. He loved to go to Fetlar, but he never seems to have considered emigrating there. His relationship with Fetlar was emotional rather than practical. His life's work was in Yell. If we want to understand Laurence Williamson we have to look closely at his family, not least his father. There is a splendid little biography of James Williamson by the late Robert Johnson, and some years ago the late Christine Guy produced a fine play about him in Yell, 'A Skoit Ahint'. My own impression of James, from reading numerous comments by his son, is of a generous but extremely private man. He married Mally Gardner, his 36 year old servant, in 1854. She was pregnant. He was 54 years old. Laurence Williamson was born a few months later, and May Williamson in 1859. James Williamson was an attentive but stern parent. He instructed Laurence to show as little emotion as possible in public. 'Beware of entanglements' with others, he said; 'keep deesel ta deesel'. As Laurence wrote in 1884, long after his father's death, under his father's regime 'I was under a Medo-Persian law ... not [to] stir anywhere without leave nor meddle with anybody or anything but my own affairs. ... Any deviation from this rule was strictly reprimanded. ... In my sister it developed a spirit of resistance, self-reliance and independence (she was almost exactly like him) but its effects on me he never would have grasped. Entirely unlike him ... but bound hand, foot and tongue, I feared to ask the least freedom, otherwise I was kindly dealt with. 'Naturally I turned to this open pleasant field, away from the hedged and thorny; the result was I remained weak, handless, unmanly, while the understanding developed and knowledge was acquired.'

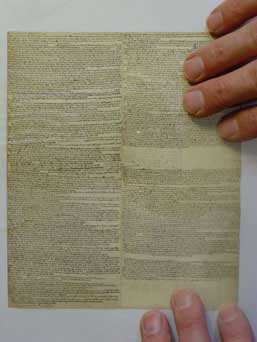

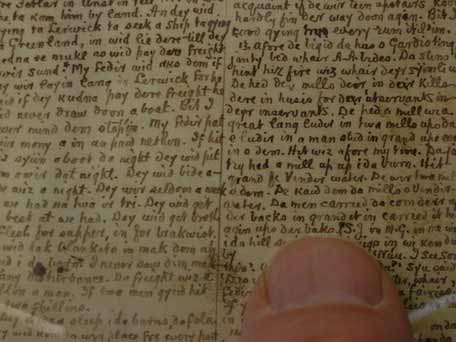

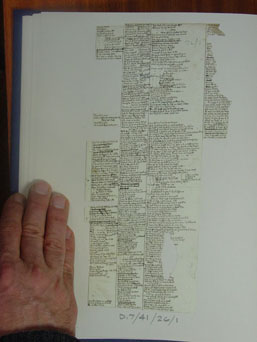

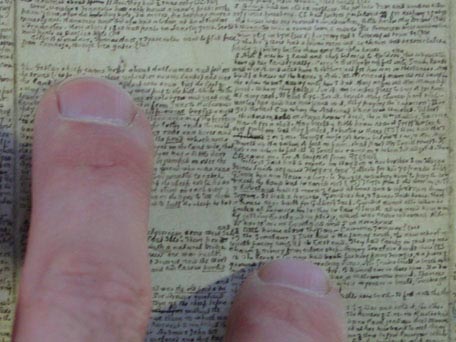

My impression when I read passages like this is of a parent-child relationship under great pressure. Years later Laurence occasionally dreamed about his dead father; he always looked stern and angry. In 1870 James Williamson's health broke down. The spectacle of a such a quiet man, whose voice the children had scarcely ever heard raised, screaming in agony, was something they never forgot. James Williamson died at the end of 1872, leaving his business affairs in confusion. 'For some years', Laurence wrote later, 'I bore the trouble by seclusion and evasion of difficulties. I was thereby much imposed on, trampled and degraded.' He took refuge in intellectual things. Laurence was the star pupil at Andrew Dishington Mathewson's East Yell school. He learned a great deal from Mathewson, including some of his bad habits. He mimicked Mathewson's trick of writing in minute characters. Mathewson was under no illusion that his pupil was something special. On one occasion J.R. MacQueen, the eccentric and learned laird of Burravoe, visited the school, and Mathewson watched admiringly as Laurence and the laird discussed Hebrew grammar. MacQueen gave instruction to bright Yell boys, notably Thomas Mathewson, and it wouldn't surprise me to learn that he taught Laurence as well. Whether he did or not, there's no doubt in my mind that Laurence was very impressed by MacQueen: he imitated MacQueen's writing so accurately that it's difficult to tell the two hands apart. As Laurence's schooldays headed to a close Mathewson wrote to James Williamson advising him to send Laurence to the Anderson Institute in Lerwick, with a view to his getting a civil service job in Lerwick or further afield. But James's death put paid to that idea, and ensured that Laurence would never leave Yell. There isn't a lot to say about Laurence's working career: the remaining 60 years or so of his life. For ten years or so he succeeded his father as sub-postmaster, and was much involved with the operation of the telegraph there, because Mid Yell was a busy herring port in the late 1870s and early 1880s. On one occasion he had a jaunt to Hillswick, to instruct people there how to use the new technology. In 1884, however, he abruptly resigned as postmaster, and devoted the rest of his life to what might be called crofting. No-one ever claimed that Laurence was a successful crofter. He was too much inclined to break off work to make some strange calculation or observation. In a letter of 1900 he tells his sister how he has 'wrought hard at the lay heads of rigs 2 and 4 (counting from east), some 25 pace each, 6 days should have done me: but many interruptions, and yesterday mostly taken up windu ing Scots-ets (9 bushel) and taking in ait-skroo which mice had spoilt--killed 29. Also last piece very bad sooriks so not finisht ...'. But although he wasn't a roaring success at it, a crofter he remained. With the exception of a short spell teaching at Ulsta during the First World War Laurence became an institution in Mid Yell as a sort of crofter-intellectual. I have to stress that there's no doubt that, as a scholar, Laurence Williamson was something special. No doubt he had excellent tuition from Mathewson and MacQueen, but he branched out on his own almost immediately. In his early twenties he began to correspond with Karl Blind, a folklorist based in London, a one-time friend of Karl Marx; Blind wrote privately to Arthur Laurenson, a scholar in Lerwick, that he was astonished by Laurence's knowledge. But it's very difficult to know exactly how Laurence Williamson organized his intellectual activities, because of the way he wrote things down. Anyone who has dipped into his papers, which were rescued after his death by Laurence Johnson, and are now in the Shetland Archives, will know what I mean. Laurence was even more eccentric than his teacher, old Andrew Dishington Mathewson, in the way he recorded information. I'll give you one truly extraordinary example. About 1875, when he was 20 years old, Laurence took a trip to Fetlar and made copious notes, from informants in the island, about Fetlar history and lore. The resulting manuscript is over 20,000 words long, about a quarter of the size of an average modern novel. The unusual thing about this manuscript, however, is that the 20,000 words are crammed onto one A4 sheet. As you might imagine, this document poses serious problems to those of us who try to read it. A few years ago the late Robert Johnson and I made a transcript of it, but before doing so we had to photograph it, using an instrument called a varimagnifinder, to ensure pin-sharp focus, and then blow it up 18 times. I've heard that Laurence achieved these strange results by writing with a sharp quill and peering at his writing paper through a powerful magnifying glass.

Few of Laurence's productions are quite as odd as that. However, very few of his papers are exactly normal in format. He seems to have selected the smallest and oddest shaped pieces of paper, or bag, that he could find, as writing material. And it was with this kind of apparatus that Laurence spent the rest of his life, writing down what he had heard from old people in Yell and Fetlar, and what he thought about life in general. There's one other point about Laurence's writing, which I hope will emerge from what I've got to say tonight. He was very beautiful prose-writer. I'll quote from a letter he wrote to a cousin in 1881, about a walk that he had just taken through the hills of Yell after nightfall: 'Still farther to the right is a giant knoll like Stakaberg. On the hitherside of it is a dim green patch. This is the hill town of Bouster. Miles and miles up the valley leftwards a dim gray hill locks up the valley like a sea-worn boulder in a great grind, and oh how lonely. ... Tonight the sky above the door like hill is of a hazy blue in which Sirius twinkles clear and aloft'. I think it would be interesting to give some examples of Laurence's views on Shetland and the world. Although he was unassuming in the extreme, Laurence had strong and fixed opinions. He loved Shetland, and the North Isles in particular: not just the scenery, but what we might call the quality of life. Writing to his sister in 1890, for instance, he mentions two women called Boyne, who had just been in Fetlar for a holiday. 'I hope the Boyne lasses are keeping well', he said, 'and better of their Shetland run. Its a pity they weren't ½ a year in Shetland, in a place like Byelagord or Still. And with rough shoes, clothes etc. for the place. It would give them a health, and a feeling of freedom and peace, they never felt before'. On occasions like these Laurence sounds like a one-man Shetland Tourist office. However, deeper ideas and feelings emerge from time to time. In 1897 he wrote, again to May, as follows. 'I've for years paid careful attention to the pictures of the life of the rich in the south, of which modern literature is so full, and am long persuaded that whatever their advantages in intelligence, knowledge, cleanliness and comfort it is far outweighed by the cares, shams, hollowness and anti-Christian social beliefs and practices that crowd and afflict their lives. The evils in Shetland are very many and great. ... Still I know that far better than all the glittering show is the life in James Hunter's and L. Brown's calm and peaceful house, or the truthfulness, sincerity, honesty, manliness and downright independence of the Norseman ...'. And a year later, after reading a fashionable novel of the time, he said: 'I was reading one of "Ouida"'s stories. It's a dangerous book, but it's an awful picture of the godlessness, truthlessness and immorality which I have good reason to believe are so characteristic of high society south, with all their intelligence and knowledge of the laws which produce wealth and beauty and comfort, with all the evils of ignorance and blind conceit. Our islands, barring the gutting-influences and some mixed places are a paradise compared'. What Laurence admired about Shetland was simplicity, honesty and fresh air. The second theme that comes out of Laurence's writings is rather more controversial. Like many of his contemporaries Laurence was obsessed by what he called 'race'. At a harmless level he spent hours tracing family trees and observing people's faces and heads. On one occasion he apparently took a small telescope to a dance in Fetlar, and amused himself by observing a woman visitor's features and, no doubt, the bumps on her head. (As Ian Tait of the Shetland Museum said to me, that probably didn't improve the conviviality of the occasion.) Laurence's writings are full of this kind of pseudo-scientific tripe. To take one example: when he was in Hillswick he was always on the lookout for handsome women. 'As to pretty faces,' he wrote, 'for a while I saw few or none. I knew there must be. Population 2,200 means 275 young faces, 66 good looking and 22 beautiful faces among them. ... 'But since I began this letter I have seen two exceptionally fine faces, both young, fair and Norse. The first, Margaret Thomasson from Bordagirt ... was slightly-grown but not thin ... fair skinned, particularly calm, but bright eyes, full flaxen hair, in a neat cloth dress. ... Her lips had a free openness about them displaying her teeth, good brows.' And so on.

Personally, I find this kind of thing distasteful. There is no doubt that Laurence, and many of his contemporaries, were obsessed with race; in the 1930s, as we all know, the results of that kind of came to fruition. All I can say in Laurence's defence is that he stressed, again and again, that he wasn't making judgments about this or that race. Writing in 1900 about a Scotsman who had just died he said: 'He had peculiarities no doubt, but they were mostly those of his race-type and environment, which the Great Judge will certainly discount.' Laurence admitted that he preferred Shetlanders and Norse people, but he admitted that they had faults. He thought that they were hasty and obstinate; he regarded his sister May as a typical Norsewoman. Writing to his cousin Thomas Hunter in 1916 he said: 'After all, my mind turns with most liking to the Norse type, in spite of their want of philosophic thinking and their terrible persistence. Their simplicity, frankness, sincerity, and their depth and persistence of affections, their firmness and bravery when need is all are most precious, and their independence and love of freedom.' As I've said, racial thought in the twentieth century has usually been deeply reactionary. In the late nineteenth century, however, things weren't so simple. Many socialists and radicals were infected by racial ideas; when they said that they liked the Vikings they thought of the Vikings as socialists, or at the very least freedom-fighters. I don't mean to suggest that Laurence Williamson was ever a socialist. In 1911 the Lerwick socialist Haldane Burgess gave him a book by Engels, and Laurence nearly had a fit when he dipped into it. But in the 1880s especially Laurence had some rather radical ideas. In 1886, for instance, there was great misery in Fetlar, when an attack of sarcoptic mange decimated the islanders' ponies. Laurence leaped to the defence of the crofters, and wrote letters to the Shetland Times , under the pen-name 'Stakaberg', attacking Lady Nicolson and her factor, Colin Arthurson. Similarly, in 1892, when the Crofters Commission came to Fetlar, Laurence acted as a representative for crofters claiming fair rents, and wrote a lengthy memorandum for the commissioners, with a history of the Nicolson family's tyranny in the island. In 1897 he refused to attend the bonfires in Yell commemorating Queen Victoria's jubilee because, as he said, it was 'an Established Church thing': 'I object to the jubilee and kingly craze as unpatriotic, seeing the destruction they have worked on Shetland and its institutions and its opposition to the Norse spirit'. Having said that, Laurence's main interests weren't political. He was far more at home dreaming about the great Norse race of Shetland, or about this or that Shetland woman. But interested as he was in family trees, Laurence never managed to produce any children of his own. That wasn't for want of falling in love. Those of you who have read Laurence Johnson's life of Laurence Williamson will have read his astonishing long love-letter of 1890 to Mary Watson. Mary had written him a 'crushing hopeless letter', as he put it. 'Tho' I would not have said it before,' Laurence replied, 'I will do it now: that besides the priceless fact that you were a Fetlar lass ... I have never seen a shapelier one than you, or a more simple unconscious and perfect grace and ease of motion. ... That first night you and your sister looked like two happy children, like two beautiful wild flowers dancing in the summer wind.'

With that off his chest Laurence looked elsewhere. On one occasion he and his cousin Thomas Hunter made an excursion to Baltasound to look at the immigrant gutters. There's a scrap of paper in the Shetland Archives where each of them has written admiring comments about a beautiful woman, and especially about her 'fine brows'; I get the impression it was written in a back pew of the kirk at Baliasta. Meanwhile he had fallen in love again, once again with a woman in Fetlar. In 1902 that woman went to Lerwick with some relatives, to have their photograph taken at Abernethy's. Laurence got to hear about the trip, and wrote to Abernethy with strict instructions about precisely how he wanted his sweetheart to pose, and what furniture he wanted in the background, presumably without her knowledge. At length she too got tired of her suitor, and wrote him a polite but forceful five-line letter telling him that she had designs elsewhere. And that was the end of Laurence's romantic career. Laurence clearly walked around in a sentimental haze much of the time. However, like everybody else, he knocked up against reality every now and again. He shared the Haa of Gardie with his mother, Mally Gardner, and his sister May, and it's worth considering how he got on with them. Mally Gardner had grave health problems throughout her life. She seems to have coped badly with domestic upsets. Whenever May went away from home, as she did from time to time, Mally dictated letters to her via Laurence instructing her to come home immediately, peppered with suggestions that she was about to die because of her unnatural offspring's unkindness. No doubt Mally was a difficult character to live with. On the other hand, Laurence regarded his mother as his main source of information concerning Shetland words and lore. Sometime in the 1880s he began to note down words and phrases as Mally uttered them, with the date and time of the utterance appended, sometimes with a short description of the weather at the time. There are many hundreds of scraps of paper in the Shetland Archives with Mally Gardner's occasional pronouncements over a period of about twenty years. We know more about what Mally Gardner was saying in the last 25 years of her life than anyone else in Shetland. May Williamson was a different kettle of fish. Laurence was like his mother; May was like her father: moody and sometimes passionate. She found it difficult to put up with her mother's constant demands, and, as I said, she left Yell every now and again, sometimes to work in the fish in Lerwick. Laurence seems to have been relatively close to May; he wrote to her once a week whenever she was away, and sometimes, when there was a delicate subject under discussion, he wrote in code. There's a long-standing tradition in Shetland that May regarded Laurence as feckless, and that she was a philistine who was itching for the opportunity to burn his papers--and that she did so. This is nonsense. I have no doubt that Laurence irritated May from time to time--he seems to have irritated everyone he met--but there is evidence that she actually shared his interests to a limited extent. Laurence often wrote to her about this or that new book about Shetland, and when Jakob Jakobsen, the Faroese linguist, was in Edinburgh in 1896 he sent him to May's lodgings there to tell her about his new discoveries. The story that May threw Laurence's papers in the fire is drivel. I can assure you that none of Laurence's papers show any signs of singeing, and in none of his letters does he make any reference to any such event.

However, things went badly wrong between Laurence and May in 1895, and with hindsight we can see that these events, which took place when Laurence was 40, as among the most important in his life. May abruptly left Shetland and took up employment as a domestic servant in Edinburgh, much to Mally's disgust. Much worse, however, from Laurence's point of view, weree reports he immediately began to receive from people in Edinburgh about the company May was keeping. In fact she was going out with Laurence's namesake Laurence Williamson, a namesake of the notorious 'Moytla' family of Yell whom Mary Helen Odie will tell you about. The danger that May might marry into this no doubt racially tainted family drove Laurence to distraction.

He sat down and wrote a letter to May the like of which I have never read before. I'll read some carefully censored and abbreviated parts of it, with individuals' names rendered as 'so and so'. From early childhood I began to know and see into this hereditary curse. I mind looking with awe as they landed so and so's dead children and hearing the cause and how she was 'rotten in the pox'; and then the inhuman tale of so and so their mother's death made me creep. ... Just think it over. Every family has blemishes, some in one direction, some in another. But this great family has been a mass of corruption. ... They are stout, often good-looking, but of a lustful type, often skilled fishers and seamen. They have multiplied beyond any family I know of, hundreds scattered around here and over the world. But everywhere they have the same stamp, the same inherited curse in their blood and vitals, it attacks all connected with them. They are given up to bastardy and adultery, and incest, and infant-killing and abortion, and druckeness and obscenity beyond all speaking and in all their branches. I could go on. Laurence certainly did. Meanwhile he was posting spies, male friends, around Leith to keep an eye on May, and receiving communiques from them at regular intervals. You can imagine the effect these events had on poor May. In due course Laurence himself left Shetland for a while. I'm not sure why; he doesn't seem to have gone looking for May, although he did visit Edinburgh. He seems to have looked for a job, and got references from some of his literary friends, but after a month he came home again. I suspect he was depressed by May's activities, and unable to cope with his mother's lamentations. He certainly didn't get much out of his only voyage out of Shetland. Seven years he wrote: 'Once Edinburgh would have been of great interest to me, but when I was there I felt not the least desire to go outside the station to see it'. In due course things got on an even keel again. May eventually parted from her sweetheart, but of course she was bitter about what had happened. She remained in Edinburgh, and subsequently went to London. She struck up correspondence again with Laurence, and he sympathised with her in her various trials. 'We are truly sorry to learn you have got such a hard-working place with such long hours,' he wrote to her in 1901. 'I am long sick of this servant girl life, it's 4 times out of 5 a slavery. ... Sooner or later it must end for it's against Christianity and the heart's best feelings for men and women to be trodden down in slavery, whatever shape it takes'. But I doubt if May ever forgave Laurence, or her mother, for depriving her of the other Laurence Williamson. The other main result of these events was that, from 1895 until she died more than ten years later, Laurence had to look after Mally Gardner on his own. She was in very poor health throughout those years, and Laurence was extremely attentive to her. Things weren't improved by her constant refusals to do what the doctor advised. She died in February 1906, and Laurence wrote to one of his aunts a moving account of her passing. 'Mitchell, Daniel and Charlotte Clark came and stayed all night and Thomasina till one a.m. She grew weaker from midnight to 4.30. At 1 she knew us all. Then her face gradually brightened and a bloom on her cheeks, and she looked much like what she did in my early years, young, round cheeked and bright. The choke kept on. But from 11 she gradually grew weaker and paler till 4.33 when the breath calmly went, as I commended her spirit into the great Father's hands. ... Tomorrow is her 87th birthday. Poor mother'. After Mally died May came home again, and looked after Laurence for the rest of her life. For a few years they continued to live in the Haa of Gardie, but in 1908, following a disastrous attempt to repair it, they flitted to a nearby outhouse. They spent the rest of their days in that miserable hovel, living and sleeping in the same room. There is no doubt that May's temper flared up from time to time; but who can blame her? Given their circumstances it's surprising that there wasn't more strife. As I said before, May Williamson has been the object of much character assassination, because of her allegedly philistine attitude to her brother's studies. I believe that she had a relatively realistic but affectionate attitude to Laurence. A year before she died she wrote to someone who had been trying to get some information from Laurence. 'My brother Laurence got your letter some time ago,' she said 'and I am sorry he has never answered it yet. ... He is an old man, 78 years old, he has always been a slow sort of fellow, only at seeking knowledge on all sorts of things which his head is full of; he would be able to tell you of your relations for generations back if he would start and do it and not keep puting of the time keeping people waiting'.

During the last 30 years or so of his life Laurence was more timid and more anxious than he had been formerly. He had clearly come to the conclusion that he would never marry, and that his branch of the great Williamson line would cease with his death. More than ever his writings are full of remarks about the death and eclipse of Shetland's distinctive culture. 'Our people now in 20 years have been melting away like the flowers before the winter,' he wrote on one occasion, 'the kind and the unkind, the thoughtful and the careless. ... And yet of all the nations and countless kindreds of the earth there was but one that was ours with all its goods and its evils--or ever can be.' He seems to have despaired of ever getting his papers into order. 'What my heart used to be in', he wrote to Haldane Burgess in 1911, 'was the preservation .. of the spiritual treasures of our branch of the Teutonic folk. ... It needs a special and long training, and I feel I could have done much had I been better situated.' To the best of my knowledge the only substantial item that Laurence published in his lifetime, apart from some newspaper journalism, is a two-page article on Shetland festivals, which first appeared in Manson's Almanac in the 1890s. Some friends tried to help him, but eventually despaired of him. One was Thomas Mathewson, his former schoolmate and one-time pupil of J.R. MacQueen. Mathewson had a little bookshop and publishing business at the South End of Lerwick, and he frequently tried to persuade Laurence to write something for his press. After years of wheedling he finally published one Williamson item: one sentence from a letter by Laurence, overprinted on a postcard. In 1908 he became an Episcopal minister at Rhynie in Aberdeenshire. He tried to coax Laurence to become manager of his Lerwick bookshop. There are a dozen letters in the Archives where Mathewson asks Laurence, who had apparently said that he would think it over, to move to town. But Laurence never did. What I've said may suggest that Laurence Williamson was an abject failure. That would be grossly unfair. Quite apart from his manuscripts, despite the difficulties in reading them, he was what I might call a good neighbour. People constantly called on him to help to write this letter or apply for that grant. He attended and occasionally participated in meetings of the Mid Yell Debating Society, looked after the public library from time to time, and acted as clerk to the grazings committee. In 1918, when he was briefly teaching at Ulsta school, he drafted a petition on behalf of the people of Arisdale, Hamnavoe, Cuppaster and Ulsta, about the need for a branch road to Arisdale. My strong impression is that he received little or no remuneration for these activities, and asked for none. In fact he seems to have had a horror of money. He did eventually begin to take the old age pension when he was 70, but he insisted on walking to East Yell to take it up. In the same way, he was extremely generous with his knowledge. When Jakob Jakobsen came to Shetland in 1893 he headed for Mid Yell to see Laurence. Laurence shared his voluminous notes with the Faroese scholar, and when Jakobsen's dictionary appeared he paid Laurence a fulsome tribute as his best helpmate in Shetland. Once again, this generosity didn't make him rich. There's no doubt that most of his contemporaries looked on Laurence Williamson as a curiosity, and there's plenty of evidence that he himself felt out of place, in Yell and everywhere else. Writing to his cousin in 1901 he said: 'In bygone Yule-times ... I have often wished you were here beside us. It is true there were rants almost every Yule-time, but I never went to them. I seldom felt more isolated than at Yule.' His main contacts with people were with a few select companions, people whom he could visit aboot da nights. On one occasion Laurence sat with the late R.W. Tait, headmaster of Mid Yell school, until four in the morning. Eventually Laurence said: 'Do you fin teachin a strain, Mester Tait?' 'No,' said Tait in surprise. 'Why, Laurence?' 'I thought you looked tired.' Laurence Williamson died in Mid Yell on 25 April 1936. A few days previously he asked Laurence Johnson to salvage his manuscripts, most of which were still in the Haa of Gardie. Johnson carefully sifted through mountains of papers and removed scraps from books and journals, many of them damp. Laurence Williamson was fortunate in his literary executor; it is difficult to imagine that anyone else would have been so careful. During the Second World War Peter Jamieson, later editor of the New Shetlander , corresponded at length with Laurence Johnson about the papers, and together they made transcripts of them. Peter Jamieson wrote several drafts of a biography of Laurence Williamson, largely based on the manuscripts; later Laurence Johnson took up a similar task, and eventually produced the book I mentioned at the beginning of this talk. Thanks to Laurence Johnson and Peter Jamieson, Laurence Williamson's life work, fragmentary and eccentric as it was, has been preserved. I hope I've given the impression tonight that I like Laurence Williamson, despite his foibles. He seems to me to have been generous and selfless in his attempts, against all the odds, to preserve what he had discovered about the history and lore of Shetland. As he wrote to a friend in 1915, 'You know there is no money in these things, but one longs to know about one's own people. ... Often while the old people are alive we can learn from them, and also preserve it for others who will want to know in future.'

- Brian Smith. Shetland Archives.

|